Grave Goods

by Greg Michaelson

1.

I left the cemetery feeling angry and aggrieved. That wasn’t about the Meg I knew. Why hadn’t they asked me?

In the car park, Meg’s partner Charlotte was waiting for me. Charlotte and I had little time for each other, each resenting how close the other was to Meg. We shook hands, in that strange British concession to physical contact, and she handed me a small packet.

“Meg wanted you to have this,” said Charlotte, and walked away without further explanation.

2.

Until her illness, Meg had enjoyed a controversial career. Her soubriquet – Mons Meg - belied her slight build, barely more robust than her aged army-surplus metal detector. She had no time for those who saw detectorists as, at best, their amateur helpmates. Rather, Meg fully embraced citizen science, always claiming to be a citizen first.

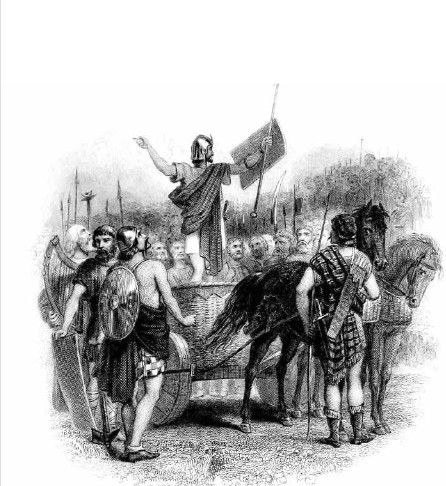

In late 1979, Meg had, against all the odds, identified the site of Mons Graupius, where the Romans finally defeated the Caledonii: hence her nickname. Ignoring the multiplicity of theories that failed to reconcile Tacitus with geographical reality, Meg, headphones beneath her trademark woolly bunnet, had spent many a weekend scouring Upper Deeside, arguing that any large pitched battle would leave metal remnants.

Sure enough, just outside Peterculter, Meg found a freshly ploughed field seeded with shards of iron and bronze. Despite establishment scepticism, she and local volunteers dug a trench across the field, revealing a huge pit filled with the long forgotten dead.

You can learn more in the Visitor Centre. Meg’s succinct monograph is long out of print. I still have my copy.

3.

At the office, I peered into the packet, and choked up.

The circular dull metal brooch, inlaid with crudely cut glass, was a caricature of a Roman design. “Fatto in Italia” was stamped on the back. Meg had bought it from the curio shop in the Apulian village near her first dig: indeed, my first dig, where we’d first met.

Meg called the brooch, which she always wore to academic events, her memento mori. When questioned, she told people that we shouldn’t forget that many of the artefacts we so reverently curate were most likely unwanted gifts. Why else had we found them?

I closed the packet and slid it into my bottom desk drawer; I’d look at the brooch properly when I felt less raw. Maybe I’d wear it to the launch of Meg’s festschrift, which I was editing. I was beyond sad that the book hadn’t been published before she had died.

4.

I’d really fancied Meg, as we’d crouched beside each other on that hot and dusty site. Once we’d established that wasn’t going to happen, we became fast friends. Our interests were very different, she in Roman Britain and I in the Neolithic, as were our approaches. She liked self promotion. I thought good work should speak for itself, and was jealous of the visibility I shunned. But we could critique each other without rancour, and could always confide in each other, knowing that our woes would go no further.

Charlotte was the one part of her life that Meg wouldn’t discuss with me. I’d long appreciated that Meg liked to keep her worlds separate; I couldn’t recall a conference where Charlotte had accompanied her. I thought Charlotte mousy and dull. Meg was all we had in common. We encountered each other infrequently, and were mostly polite.

5.

As the semester progressed, the brooch haunted me. I spotted the packet every time I opened the drawer, infrequently enough for it to always catch me out. But the longer I left handling the brooch, the harder the prospect felt.

I felt a wry amusement at my complicated relationship with the brooch. Meg wore it as reminder of how transitory our lives are: how little possessions signify once disconnected from their contexts. But, for me, the brooch represented our long years of friendship, and signified how much I missed her. I now wished it had been buried with her, for future archaeologists to ponder over.

6.

Once teaching had finished, I chivvied my fellow festschrift authors, trading on guilt at our collective tardiness. When I’d finally signed off the proofs, I set about organising what was now to be Meg’s memorial. All the authors had agreed to speak. The University provided a lecture theatre: the Department the reception.

Instead of name badges, I decided to give copies of Meg’s brooch to the attendees. I passed the still uninspected packet to Sam, our technician, who scanned the brooch, and set up a 3D printer to slowly churn out copies.

I was impressed at how well this process captured the kitsch shoddiness of the original, even if the cut glass was now clear plastic, and the back read “Made in Scotland”. My expectation was that these tokens of Meg’s humility would become badges of hubris. That would certainly have amused her.

7.

On the morning of the memorial, I finally took the brooch out of the packet, but I barely glanced at it before I pinned it onto my lapel. Now it would be just one amongst many, special to me, but no one else.

The event was well attended. From the podium, I spotted Charlotte in the back row. Of course I’d sent her an invitation, but I hadn’t expected her to attend. I now regretted not consulting her about the afternoon’s agenda.

I’d wanted Meg’s memorial to be far more celebratory than her funeral. And, without prompting, her peers spoke of her with affection and respect, appropriately tinged with exasperation at her contrariness. The only teams Meg played with were the ones she captained.

The reception that ended the event was noisy and good humoured. But, throughout, Charlotte sat near the window overlooking the quadrangle, sipping from a tumbler of fresh orange juice. It was clear that she knew none of Meg’s colleagues, even though many had known Meg for almost as long as I had.

8.

Feeling responsible, I left the huddle, and went to sit next to Charlotte, pleased that she was wearing one of the brooches Sam had made.

“I hope that was alright,” I said. “Not too dull.”

“Of course not,” said Charlotte. “It was all most fitting. I knew she had to be a significant figure, even though she left all that behind at our front door. Well done.”

“Thank you,” I said. “That she was.”

We sat in silence, more awkward than companionable.

“I never thanked you properly for the brooch,” I said, finally. “I see you picked up one of our knock-offs.”

“Oh no,” said Charlotte, fingering her brooch. “This was Meg’s. The one she bought on that dig with you, all those years ago.”

“It can’t be,” I said. “Look.”

I unpinned my brooch and turned it over. To my confused astonishment, the back was blank.

Smiling, Charlotte took off her brooch and handed it to me. The back read “Fatto in Italia”, just as I’d remembered.

“If you’ve got the one she bought,” I said, “then what’s this one? Another copy?”

“Oh no,” said Charlotte. “It’s an original. Going on 2000 years old. Meg said they were likely produced for Roman tourists. They’re mostly in collections now, though. She spent ages trying to find one for you. She’d always meant to give it to you herself.”

I looked at my brooch, and I looked at Meg's. Then I looked at Charlotte.

"Might we swap please?" I asked.

"But she wanted you to have that one," said Charlotte.

"I know," I said. "I know."