A Spell Of Watching + 4

A Review by Anne MacLeod

A Spell Of Watching

Hamish Whyte

Shoestring Press (2024) £11

Brother

Sheila Lockhart

V Press (2023) £6.50

Briny

Mandy Haggith

Red Squirrel Press (2023) £10.00

Poems, Stories and Writings

Margaret Tait

Edited by Sarah Neely

Carcanet Classics (2023) £14.99

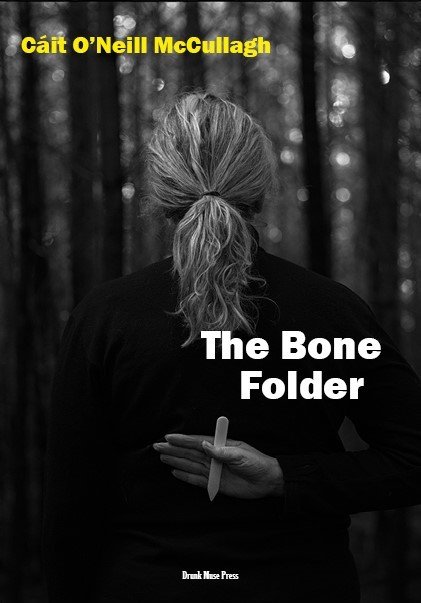

The Bone Folder

Cáit O’Neill McCullagh

Drunk Muse Press (2024) £10.00

In A Spell of Watching, New and Selected Poems, Hamish Whyte offers a collection that celebrates and delights. These beautifully formed poems, deft and elegant, reveal a lifelong passion for nature and family. He writes eloquently of love, of history, of changing times – always anchored, as in the title poem A Spell of Watching, to his fascination with life itself:

‘I/am anchored/I cannot clap my hands under the spell of watching’

Whyte is a natural storyteller with a clear appreciation of the complexity of simple language and, beyond this, an unerring gift for rhythm; he is, after all, also a drummer which may explain in part how perfectly the poems – mainly free verse – are laid out, the reader’s eye exactly danced across the page. He can surprise. Apparently quiet poems will burst into unexpected beauty, as in Siva in Lamlash where

‘There’s a rainbow/at the foot/of Bungalow/Road./’

Other times he’ll reach unexpected philosophical conclusions. In Pot Luck

‘..Every answer/is an answer./When in doubt, doubt/’

A handful of medical poems hit the spot. First Day in Hospital, a highly effective list, should be read by every medical student, and Where’s Jemima McGregor? leaves us wondering, like Whyte himself, about that disappearing lady.

There’s humour too. In Argument, his teenage self is

‘/..ground on/ intent on getting it right/’

And in Guiser, he’s running children home at Halloween, when

‘/we passed a fox at the/ Crossmyloof Station lights/ waiting for the green man./’

This collection, you’ll have gathered, is a broad-ranging delight, a sifting of decades of work. It’s much more than a collection – it’s a finely woven tapestry that, as in the lovely Cornwall To Glasgow (written for Edwin Morgan,) has Whyte

‘/Waving my hands/raising my voice –/the splash the light/’

The splash.

The light.

Brother

The beautifully produced pamphlet Brother by Sheila Lockhart opens with Prologue – Angels, in which a host of advent angels appears not glorious, but

‘/long substance-less things/no wings, pale faces…/’

It is dedicated to the poet’s brother Simon, and in these pages his life and death, and his sister’s grief and gradual journey towards acceptance, are faithfully recorded. Some of these poems, under the group title Elegy for a Lost Brother, appeared in an earlier edition of Northwords Now (Issue 38). One of these, Reciting Betjeman, describes their meeting in a pub named the The Old Ship, and the poet’s hopelessness as they part.

‘/I watch you bear your loneliness back home,/shoulders sagging underneath its weight./’

In Aldeburgh Marshes (2) after his death she notes ‘/Piercing cry of the Redshank./ Let’s brush frost from the reeds./ See it sparkle silver in sunbeams./’ In Gaelic culture, the redshank and its keening cry – pillilliu – were associated with bearing souls to the underworld.

Lockhart clearly revels in the natural world. Though she now lives on the Black Isle, she grew up in Suffolk. A former art historian and social worker, she started writing after her brother’s death, and has spoken movingly about her experience on the Mikeysline Podcast. She has healed, but gradually.

In Melting Snow she owns

‘/Over time/I grow a narrative/irrigate and hoe/yielding harvests of familiar sentences/’

And in Little Buddha she imagines being able to have

‘/eyes open just enough/to let in some light/’

The V. Press blurb on the back of this book terms the poems a ‘heartfelt and unflinching consideration of grief and healing after suicide.’ They are all that. And they are very fine poems.

[Both the reviewer and Editor would like to note that any Highlands and Islands readers affected by the content of the above pamphlet can find help available through both Mikeysline and the James Support Group]

Briny

Mandy Haggith is a woman of many parts – poet, novelist, environmental activist. Musician too, philosopher, mathematician, and most of all, lover of the sea.

I should own at this stage my unfortunate tendency towards seasickness rather than sea fever, but had I read Briny earlier – much earlier, in my growing years, perhaps – things could well have been different. This persuasive, loving, questing immersion in salt water and northern fragility might then have convinced me. As it has now.

The voyage begins in Assynt, in Loch Roe, and Haggith follows Pytheas to the far North, cataloguing on the way the beauty and danger, also the environmental damage, man-made, inevitably encountered. Did not the Oystercatcher – Gille-Bridhe warn us?

‘/‘Bi Glic, bi glic, bi glic!’/which means/‘Be wise, be wise, be wise!’/

We have not been wise and yet still find beauty in Noorderlicht

/A harp, rigging strung,/soloist in an arctic concerto/’

Haggith’s spare and easy style may offer, as Ian Stephen declares, a ‘sailor’s log-book of observations’ but her wise eye and skill with word and line are clear in every detail. Playfulness too. Some poems, like Shore, offer a pleasing double structure, can be read horizontally or vertically, with subtly different meaning. And her choice of words, of consonants, reflect the physicality of the boat, the climate, as in Stormbound where

/It begins with whistles and whines of wind in wire./ Warps creak on cleats/ moaning at the limit of their stretch./

Whether you are a sailor or not, Briny is a book to read and re-read; its environmental plea firmly yet gracefully offered.

Poems, Stories and Writings

And briefly: Sarah Neely is Professor in the Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies at the University of Glasgow. Her selection of Margaret Tait’s writing, re-issued a decade after its first publication, re-introduces a woman whose life-force is undeniable, drawing together the diverse fields in which she worked.

Anyone visiting the Pier Arts Centre in recent years will be aware of Tait’s talent and the sheer force and flood of her ideas whether expressed in film, or on the page – all this funded by locum work in General Practice up and down the country, though her home, for the main part, remained in Orkney.

In this inspiring book, the stories and poems are fresh, surprising and current. Margaret Tait had so many ideas and developed them with energetic dedication. One of her poems speaks to this. In A Fire

/The tiniest twigs will nearly always light,/Even if they’re wet,/

It obviously worked for her.

The Bone Folder

Creating a poetry collection is not a simple layering of gathered work. It takes a great deal of creative thought. And it’s different from actual composition: two fine poems laid side by side may sometimes undermine each other, simply implode. This is never a problem here. Cáit O’Neill McCullagh – archaeologist, ethnologist, essayist – knows what she is about, and confidently opens her first full collection with a quartet of useful definitions. Bone folder (noun) 1. Tool used to score, flatten and smooth folds with delicacy 2.One who turns the bones 3. A strong medium, creased and folded 4. A holding space.

The Bone Folder of the title proves to be a prose poem with ancient yet futuristic echoes. A woman who is undergoing chemotherapy returns home each night to sift a box of memories, precious mementoes of her past and possible future. She carves this history for meaning, for healing, using only a bone tool, a bone knife –

‘/haunted, the hare springs/her winter skin: finds a form/ in her own ghostings./’

Any and all of the definitions stated above would apply.

The first poem of ‘the collection warns us that ensuing pages will not necessarily prove a comfortable read. Charm of the Bones declares that the song of the lost bones is iron on stone, and that

‘/It is by the nettle/ you know us, urtic-sharp../’

This is necessary. The initial swathe of poems dealing with the poet’s cancer diagnosis and surgery are set against the backdrop of the Ukranian war. In Odesa, a father watches his children and partner leave the war zone, weeping. No words to help. In Eighteen Words My Gynaecologist Whispers the poet re-interprets the language of medical consultation.

‘/Found/ three masses/ ( I think cancer, but no-one says it)/’

The cancer journey, the war, continue through the first third of this book but even in bleak times the poet stretches for the lyrical. Prior to surgery, when an anaesthetist asks her to name Ten Ordinary Things, she remembers

‘/In a room I’ll never quite recall: yarrow; an open window/the marram that bladed our flesh; in Embo - dandelions./’

Her subject matter may be serious, but McCullagh assures us hope is never, can never be, lost.

‘/In all the wounds that fray us/ hope seeds refusal./’

24th February 2022 ( A White Stork Sings)

She is much concerned with time, how it affects us all – ‘history’s hurtle’ (At Loch Currane, 1965) – and after the storm surge of illness and war, goes on to celebrate her Irish family, their strength, their immersion in recent history. Her love for family is deep. In Solas, a lament for her father, she imagines him travelling after death to a winter house where

‘/..he will hang-up his life-heavy heart/ and lift to himself amber-cradled time/in him it will become fire/’

McCullagh is a considerable talent who came to poetry only recently, in pandemic years. She delights in language, in choosing the exact and only word every time. She uses Scots and Gaelic too. And previous study can also inform the text. The odd, possibly archaeological word creeps in here and there, a mention of cherts – flint scrapings – ( At Acragar) and, once, stratigraphy. ( At the Well.)

She loves form, plays with it. She has lived (mostly) in the Highlands since her late teens, and Irish and Highland sensibilities are clear, often merging in lyrical free verse. But My Uncle Wearing a Blue Beret 1982 is a rhyme-free sonnet, Ten Ordinary Things an unobtrusive pantoum, and the lovely Curlew, a lament for the unborn, a winsome use of the reverso.

This impressive first collection is both sobering and heartening. Cáit O’ Neill McCullagh is a poet to watch, a poet of energy and sensitivity who loves life, questions history: who recognises, surely, the power of the present, but a writer who redrafts time into holding space.

Her bone tool is poetry, is language itself.

↑