The Story of Deirdre

by Kenneth Steven

When I was growing up in Highland Perthshire we would have a ceilidh, every now and again, and always when my sister visited. We sat around the open fire after dinner, however many of us, my mother with her guitar and sometimes my sister with her tin whistle. We sang the same songs time and again, but always we finished with my mother’s rendition of Deirdre’s Farewell to Scotland. She must have learnt it in turn from her mother who spoke and wrote Gaelic fluently and who had grown up in Strathconnon. She and my mother had a veritable treasure chest of Highland songs and sang in both Gaelic and English, often at the Mod.

I knew the story that lay behind the song well enough, or thought I did. I knew certainly my mother’s claim that this was Scotland’s oldest song. The beautiful Deirdre had been intended for the high kind of Ireland but she had fallen for young Naoise and he had snatched her away to the west coast of Scotland. There they had lived in safety and happiness for a time before emissaries came from Ireland to find them and assure them all was forgiven so they could return to Ireland. Of course it was a trick and they were killed when they came back. This was Deirdre’s lovesong to Scotland, to Alba, for she had never wanted to leave and would not have done so at all had she not gone with Naoise.

I carried the story and the song always: they were like the imprint of a fossil in the heart. I didn’t do anything more than carry them with me, though: for a long time there seemed little more I could have done with them.

Then my life was turned upside down and I found myself leaving Highland Perthshire, the heart of Scotland where I had spent the first decades of my life, and a marriage, to live on the west coast of Argyll. But it was far from a sad leaving because of the new story and journey of love that had been given to me, and despite all the obstacles I had feared might render it impossible. And close to the place that was to become a shared new home was Glen Etive. I remembered at once how the Gaelic name for Glen Etive was mentioned in the song my mother had sung, how this was supposed to have become home to Deirdre following her exile from Ireland.

It was those two things that came together: this new and wonderful journey in my own life and the sudden remembering of the song and the story behind it. I’ve had a contstant battle to write long poems: outpourings of the short form presented no challenge, but composing something that was a full page in length or longer, that was difficult if not impossible. It seemed akin to a stream running into sand and in the end drying up altogether; the intensity there had been at the outset always seemed to fade and be lost. I battled to find some way of telling longer stories and got there in the end by creating sequences. They were short individual pieces of poem put together to create a journey, a story. Eposodic links in a chain; beads for a single necklace – however you chose to express it. But it was a way nonetheless of creating longer poems, and that was what mattered. This is the first such segment from my sequence Deirdre of the Sorrows:

A bird came to her window sometimesand she wished she might unhinge the slit of glass to let him in. An eye watched heras she set her chin on her hands and watched him back. Most likely he wanted the fragments of her bread; the bird vanished into the green garment of the woods for ever when she gave him nothing. And then she waitedfor sun to tip the branches, and the full lightto set on fire the chamber that was hers.A girl with a twisted mouth and half a handbrought food and water with her frightened eyeseach dawn, each dusk. Otherwise she spoke with silence all day longand only watched the woods for shrieks of jays.At night when the world froze and the skies danced with a thousand bits of dustshe felt like a child, home awakening in her heart, and heard her mother calling uselessly across the milesher name; the sadness of her name.

I worked for however many months on the sequence. As with the first one I had written, A Song among the Stones, that told the imagined (but very likely) story of hermit monks leaving Iona in the 7th Century to voyage north to Faroe, Iceland and even Greenland, I wrote it in fits and starts. I would think the story was finished, had been told in its entirety, and then a new fragment would come to me and would demand to be written. With the Deirdre sequence I wanted all my focus to be on Scotland and the love story that Deirdre and Naoise shared during their time here. This is the glowing bell of amber they enter to find one another. The world falls away, and with it their fear over what may happen, over all that may lie ahead. Somehow they are out of time for those amber days that are given them, for every precious drop that is theirs alone to catch.

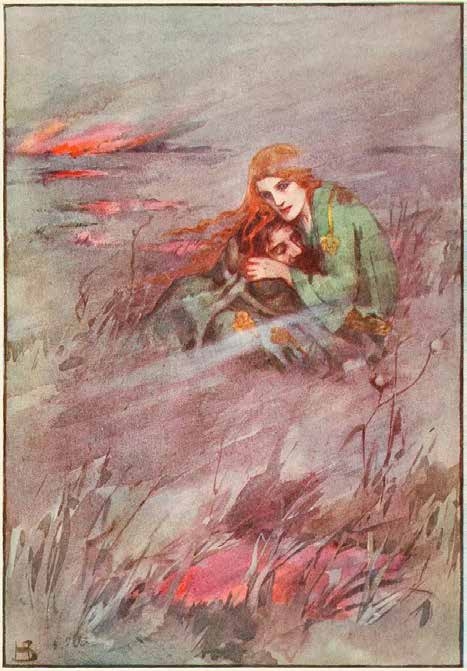

I was doing little more than following the first story given me all those years before by my mother. What mattered more than anything was the story of Scotland, of escape into safety and happiness. But Naoise has to rescue Deirdre from the captivity I am describing in the opening fragment: in my version of the telling he spies her in this tower in the forest where she has been incarcerated by the high king. Naoise has to decide to steal her away, and she in turn has to decide that is what she wants to happen. It mattered to me that the last part of my version of the telling should be conveyed as swiftly as it could be. Deep down the lovers have known surely what awaited them. But even in the last segment of the poem they are together as they await death: their bond is not broken:

I’m here, he whispered and found her in the darkness.They touched and held, as once they did that first time, the tenderness no less.

It’s no different now to when I used to hide hoping to glimpse you in the tower. He smiled.

He held her. All of it was worth our journey.There is nothing to regret. They cannot take from us all we have been given, all we have found.

I want to remember your scent, she said,so when we waken in the next worldI will know you. Softly, they kissed.

She sat up and looked at him: And there we will have our child,the one that should have been.

Both sequences were publishd by Birlinn. As with A Song among the Stones, I looked to work with musicians to perform them. Simply reading long sequences of poem and offering them as one unbroken narrative felt somehow akin to giving dry pieces of bread. In the spaces in between each segment of the narrative there was room for music, and the playing of music allowed a distillation of the words that had been spoken. For me, anyway, it was about going back to earlier times when bard and harper worked together, where music and spoken words were lifted in turn by the other. And for me there could be no more powerful instrument through which to achieve that than the clarsach, the Celtic harp.

But having ‘found’ the Deirdre sequence and seeing it printed now on the page, I somehow realised the journey wasn’t done, that it had only just begun. I listen to a great deal of radio, and after hearing a programme from RTE in Ireland, I resolved to contact the producer, Claire Cunningham. I’ve written and presented many poetry features for BBC Radio over the years, and I felt sure the Deirdre story was one that would be of appeal on both side of the Irish Sea. The poetry window is small all the same, and every year I have the sense of it growing smaller as ever more budget is devoted to entertainment and froth. Anyway, I duly contacted Claire Cunningham and after however long heard to my joy that the pitch had passed through the many necessary hoops of fire and that the programme had been commissioned.

What I looked foreward to more than anything else was the chance of talking to historians and literary scholars about the possible roots of the Deirdre story. Was there evidence those roots had been real, or was it little more than a beautifully tragic story invented for the creation of the kind of songs so beloved by the Celts? As my mother used to say herself at the ceilidh by the fireside, the Gaels were never happier than when in the depths of mournfulness.

It was a privilege indeed to see the story printed in an early manuscript kept at Trinity College in Dublin. What perhaps should have come as little surprise was that in this version Deirdre is little more than a minor character. She is at the constant mercy of the men of power around her, and almost a footnote in her own story. Nonetheless, hearing the words of the story being read aloud in early Irish by Christina, one of the experts in the provenance of those early manuscripts, is something I cannot believe I’ll ever forget.

What I discovered during the several other discussions I had with Irish scholars was that the Scottish part of the story, that which resonated so very much with me and which I had chosen to amplify as I had, was almost completely overlooked in the early Irish manuscripts. It wasn’t entirely ignored: the sojourn in Scotland was certainly acknowledged, but passed over quickly as though it was of minor relevance.

It was only when Claire and I returned to record interviews in Scotland – in Argyll and in Edinburgh – that colour came to the cheeks as it were of that Scottish part of the story. Nor will I forget easily standing on the shores of Loch Etive with John Macfarlane, one of the great living scholars of Argyll Gaelic and its cultural history, as he pointed out place after place that had a name from the Deirdre story. It seems more than than likely that Deirdre and Naoise did not come alone to Scotland: instead they travelled with his brothers. Perhaps they did so for safety and even more likely through sheer necessity.

I think what I found most moving of all was learning in Edinburgh, through speaking with Irish and Gaelic scholar Deirdre ni Mhathuna, that the great scholar and collector of ancient oral treasure Alexander Carmichael was given two versions of the Deirdre story on Barra. It’s the power behind that fact: fragments of the story of Deirdre, almost certainly rooted in the Iron Age, had been handed down like precious pieces of an ancient and beautiful garment, from mother to daughter and from father to son. Century after century after century.

Of course the story has grown arms and legs and wings over those centuries. And of course it’s likely the archetypal prophecies that make the drama of the story into a crisis have been invented and added. But for me there’s far too much smoke for there not to be traces of a real fire somewhere deep down. The very song that began the whole journey, the one sung by my mother and made famous by Marjory Kennedy Fraser, is based on ancient verses recording Deirdre’s farewell to the places she and her lover Naoise had known as home in Scotland. She describes them tenderly and intimately, as though from the vessel that is taking her back to Ireland and to death.

Dearest Alba, land o yonder,

Thou dear land of wood and wave;

Sore my heart that I must leave thee,

But ‘tis Naoise I may not leave.

O Glen Eite, O Glen Eite,

where they builded my bridal home;

Beauteous glen in early morning,

Flocks of sunbeams crowd thy bower.

Glendaruel, Glendaruel,

My love on all whose mother thou;

From a cliff tree calls a cuckoo,

and methinks I hear it now.

Glendaruel, Glendaruel.

My thanks to all those, both in Scotland and Ireland, who helped build my knowledge of the Deirdre story over the summer of 2022. I’m deeply grateful.

↑